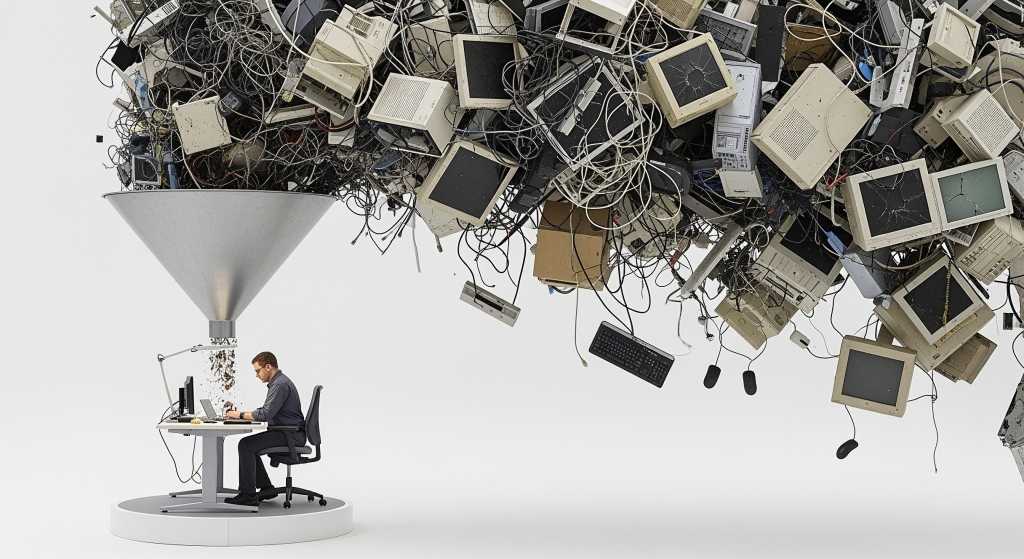

When CIOs trim the vendor list, a strategic approach can help unlock savings, while building a foundation for more tailored services and efficient operations.

Technology sprawl is a major challenge, with IT professionals feeling the pressure to manage costs, disconnected systems, and point solutions across the organization. In response, CIOs work to consolidate vendors seeking cost savings and operational efficiencies.

While traditional consolidation efforts start with assessing vendor capabilities, seasoned CIOs employ various methods to tame the sprawl. The goal isn’t just to reduce the number of vendors, it’s creating a technology foundation with better oversight, scalability, and efficiency.

1. Balance capability building with cost reduction

While cost reduction is an obvious benefit of vendor consolidation, experienced CIOs understand that building stronger capabilities and reducing tools strategically can help secure and strengthen the organization.

“I’m not looking to just remove services. I’m looking to enhance services, whether that’s cell phone services or two different ERP systems right between two departments,” says Scott Klein, CIO at TVG-Medulla.

Klein has found it useful to align with finance to uncover duplications, redundant technology, and underused tools by comparing outgoing costs. His advice is for CIOs to get comfortable with the numbers. “Be able to read a balance sheet,” he says.

When reviewing capabilities, if there’s overlap between multiple services, it calls for investigation to understand whether those services are delivering value or if the overlap is just wasted dollars. Klein will audit accounts looking for multiple services and aim to reduce any duplication down to a single supplier that enables IT to have full oversight. He identifies where services are being delivered to different departments via separate accounts and has found they’re often initiated from within that department without the direct oversight or approval of IT.

“Anything more than zero is rogue IT as far as I’m concerned, and we can go from there and have that holistic corporate approach,” Klein tells CIO.

But the work is more than just perception. It’s assessing and reducing technology, while delivering functionality and operational efficiencies. It helps with buy-in across the organization and shows IT is a business enabler.

“Be an efficiency expert or an operational expert, not simply a cost cutter,” he says.

2. Adopt a systematic assessment process

Beyond Bank, one of Australia’s largest customer-owned banks, wanted to modernize its IT infrastructure, strengthen resilience, and improve customer experience. To raise the maturity and capability of the organization, CIO Stevie-Ann Dovico has overseen a process of reviewing vendors and services as part of this uplift.

“We did quite a lot of simplification and automation,” she says.

Dovico follows the principle of seeking both internal and external perspectives to compare and validate her own assessments from the start. Doing so avoids tunnel vision in assessing capabilities and value. “Something as important as fixing the fundamentals of your organization or getting the basics right needs an external perspective,” Dovico says.

She also makes her own observations and recommends CIOs “walk the floor” to see directly how technology is being used. She spends time listening to people explain how they’re using certain tools, diving into the current state of play beyond the spreadsheet.

“This gives you a base of facts to then identify core competencies, what we’re able to do ourselves, where it’s efficient for us to do things ourselves, and where we need external support to help us get it done,” Dovico says.

Part of a systematic assessment also involves filtering out distractions during the evaluation process. David Weisong, CIO with Energy Solutions, has learned to avoid the “town hall” sales pitch approach when reviewing technologies.

Three years into his tenure, Weisong saw the business growing rapidly, going from two offices and 120 people to more than 500 people and six offices in 40-plus states. It’s also become a remote-first company. “It’s been a case of adding to our complexity while simultaneously trying to limit that because it means managing a lot of different vendors,” Weisong says.

Having found himself in meetings where an account manager, director, technical person, and even a VP are on the call, Weisong now rejects bloated sales pitches that overlook his priorities and wastes time. “I don’t have time for these meetings,” he says. “Plus, we’re not getting to the things I want to talk about because if I mention something, I get pulled off topic by one [of the many people on the call].”

3. Reduce complexity across the tech stack

Behind every sprawling vendor relationship is a series of small extensions that compound over time, creating complex entanglements.

To improve flexibility when reviewing partners, Dovico is wary of vendor entanglements that complicate the ability to retire suppliers. Her aim is to clearly define the service required and the vendor’s capabilities. “You’ve got to be conscious of not muddying how you feel about the performance of one vendor, or your relationship with them. You need to have some competitive tension and align core competencies with your problem space,” she says.

Klein prefers to adopt a cross-functional approach with finance and engineering input to identify redundancies and sprawl. Engineers with industry knowledge cross-reference vendor services, while IT checks against industry benchmarks, such as Gartner’s Magic Quadrant, to identify vendors providing similar services or tools. As a CIO and in advisory roles, his method has reduced vendors and resulted in cost savings of at least 20%.

Vendor sprawl also lurks in the blind spot of cloud-based services that can be adopted without IT oversight, fueling shadow purchasing habits. “With the proliferation of SaaS and cloud models, departments can now make a few phone calls or sign up online to get applications installed or services procured,” says Klein.

This shadow IT ecosystem increases security risks and vendor entanglement, undermining consolidation efforts. This needs to be tackled through changes to IT governance.

4. Synchronize contract lifecycles with financial cycles

In any consolidation project, contract terms with new vendors will be an important component. Many will offer long-term contracts with the lure of price discounts or other incentives, but seasoned CIOs know they don’t have to take the bait. Instead, they can insist on terms that suit their business.

Weisong has spent the past three years ensuring the clean energy consulting firm is running best-in-class solutions and moving all IT contracts onto a consistent renewal timeline.

While the size of the business doesn’t enable it to negotiate multi-seat discounts, Weisong insists on contract renewals according to his time frame. He estimates it’s about an 80/20 split, with most renewing at budget time. “I moved all of our contracts into the beginning of the fourth quarter. I’ve made it very clear; this is how we’re going to do our contracts. That way, I know I have contract season and can prepare for it,” he says.

The Q4 timeframe helps manage any hits to the budget with upcoming price increases. “The reason I do it at the very beginning of Q4 is if I end up with price increases or things that will substantially impact the budget, I’ve only got a month or two where that’s going to impact the current fiscal year and there’s no surprises,” Weisong tells CIO.

He also limits the renewal horizon to 12 months to tightly manage the value the technology is delivering to the business and because the technology itself and the larger business environment is changing all the time.

“We need to do that evaluation against other solutions in the market and the vendors we choose need to earn the right for us to stick with them, not because we have a contract, but because we’re deriving business value,” Weisong says.

5. Leverage external forces as catalysts for consolidation

IT leaders often approach vendor consolidation as an internally driven efficiency exercise. At other times, organizational inflection points such as M&A activity, new compliance requirements, and changing needs of customers create opportunities for reducing the vendor portfolio.

In Weisong’s case, it’s the increasing complexity of the business, including a growing footprint of offices and staff, more diverse client base, and software requirements to support its operations. The expanding array of compliance and client requirements has driven the adoption of security control frameworks such as SOC2 and NIST. “As we have matured as a company, so have the requirements of our clients,” he says. “When we sign our MSAs and our task orders, they come with an ever-increasing list of requirements.”

Weisong has steered the adoption of a new ERP system and reduced the software catalog from 120 to around 105 applications, including consolidating videoconferencing platforms from three to one, and cloud platforms under one primary provider.

Weisong purchases only the number of seats his company actually needs, is willing to switch vendors if they can’t meet their requirements, and evaluates vendors based on the business value they’re delivering. The approach is proactive, strategic, and focused on maintaining flexibility. It extends right through to streamlining interactions with the vendor and avoiding the upselling.

“I want one contract and one point of contact, and I don’t want to talk to you unless I need something or something’s wrong, because otherwise it’s, ‘Let us sell you our such-and-such services,’” Weisong says.

6. Address the human side of technology decisions

Beneath the technical and financial drivers of vendor consolidation lies an underestimated force: the human element. In any program of vendor reduction, IT leaders will need to tackle resistance to change, as well as attachment to certain technologies and ways of doing things.

“You have to understand that people have an emotional attachment to work and this is part of the journey,” says Klein.

It might be engineers resistant to moving from multiple cloud providers, polarized views about adopting AI, or reluctance to replace everyday software applications. Change management and communication are critical to successful technology transitions.

“It’s very easy for me to make the decision and say, ‘It’s the better piece of software,’ but it’s our employees who can spend hours a day using something,” says Weisong.

In some situations, he will lean into the cost implications of holding onto certain technologies that people are usually unaware of when they’re not privy to IT balance sheets. “I’ll explain that we’re a small company, and we do pay bonuses, and that money saved just drops to the bottom line of profit,” Weisong says.

In Dovico’s experience, it’s difficult to move forward with a program of improvement without being transparent. When CIOs shy away from difficult conversations, particularly with the board, it prevents an honest assessment of the state of things, the first step in making changes.

“It’s a hard conversation to have with the board, especially if you’re new, to say, ‘We’ve done this assessment and here are the problems we need to solve,’” she says.